“My work can be understood through the mind, but it is best felt with the heart, experienced through the emotions, recognized as a manifestation of the spiritual that is born on the picture plane. The ambiguity of the image is central to my expression of life in art.”

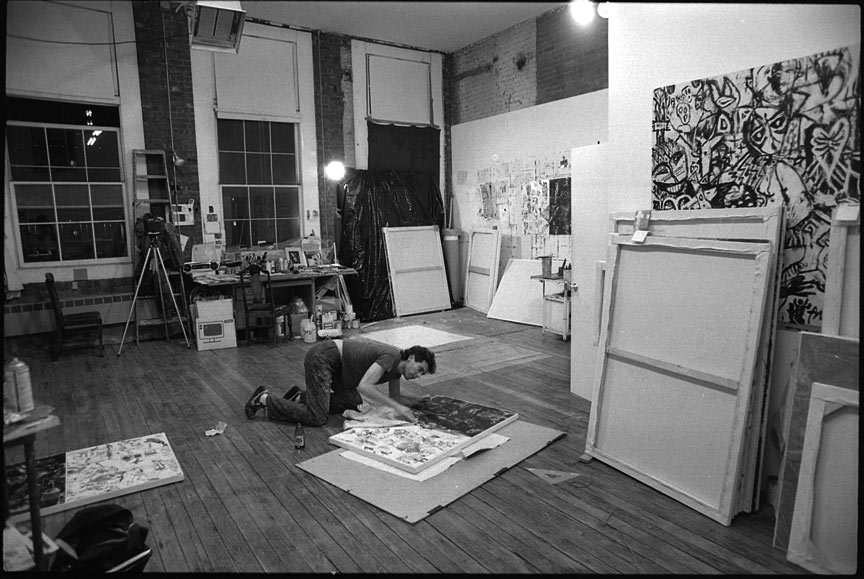

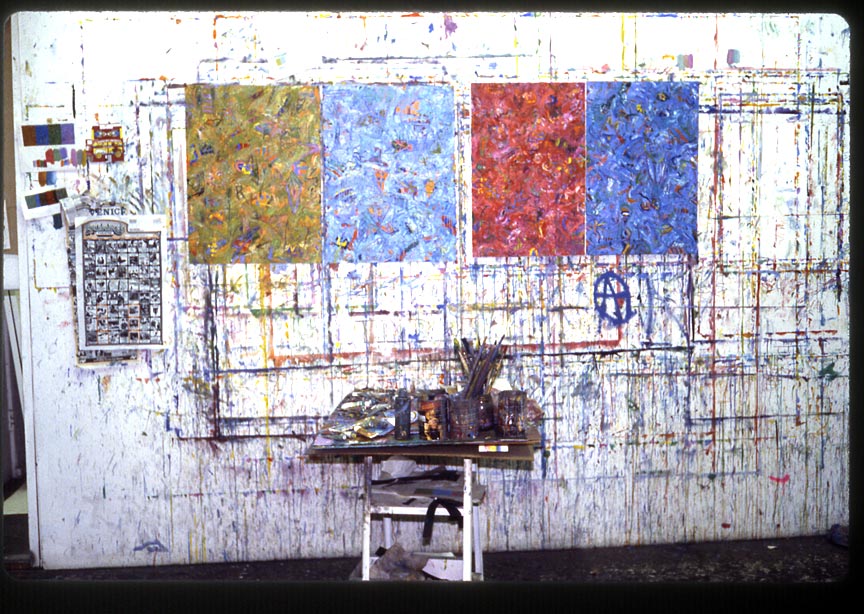

It is terrifying to paint. When you start out, you are faced with this great unknown. And you think, am I ever going to paint again? Yet, as you work, it starts to formulate itself. Ultimately every work really just decides itself. I love to paint. I love the smell of paint (oil) and the way it does different things depending on how you apply it. I love how if you use a lot of turpentine, it forms these rivulets like streams in the desert. Acrylics just can’t match the intensity or viscosity of oils. In early days, I painted landscapes and portraits, but I tried to infuse them with my own nomenclature. The colors, brushstrokes, and marks that I put on a canvas transfigure into a profound sensibility that I cannot deal with in any other way. And color is a way of expressing my emotions, and the way it is planted in my works helps tell the story.

When I was a boy I drew incessantly. I had sheets of paper roughly 10 by 15 inches, and I covered them with Civil War soldiers. Literally hundreds of them, each drawn with the same delicacy as if they were alive. Later I advanced to WW2, with German soldiers attacking the well-meaning but hapless British, grey against ochre, tanks and explosions, and beautiful landscapes where it happened.

As I became older, I wondered what it was that had so intrigued me with these war scenarios. I became fascinated with the symbols, icons and pictograms that were behind these historic conflicts. They had a substance and meaning for me that far outweighed their prescribed meaning. A cross meant Christianity, but in the films of Sergei Eisenstein, there was a distinction between the Teutonic knights with their iron helmets invading the Russian orthodox warriors to the east. A cross could mean many things, we bow down before a cross, but are repulsed by a swastika. Yet they are related. If you cut the corners of a circle with a cross bisecting it, an early Christian icon, it becomes a Sulfot cross, and then a swastika. In the hands of the Nazis, a symbol of profound evil.

Symbols have an intrinsic power; a drama and mystery that fascinates me. I became bewitched with how symbols invade and influence what we believe and think about who we are. This sensibility became the fodder for my painting.

What makes painting so interesting to me is that there are multiple realities, multiple interpretations possible. What gives the painting a life of its own is that everyone is seeing something different based on their own experience, that way, to the viewer, the painting has a continued life. Some paintings will just resonate with you, when the symbols and pictograms, and icons have this rich elegance, the piece works. It means that the symbols and icons we are subject to daily, vastly influence our lives in a way we are totally unconscious of. And that is what has importance for me. It determines and manifests in our lives and in my work an unconsciousness that I am not cognizant of in my normal day-to-day existence. This is where my art stems from. It is subtle but real, and infects me like a disease. I try to find why and how these symbols and icons have such a powerful and meaningful reality in my life.

How do we see ourselves in any kind of personal integrity, how do we form a sense of Self and Identity without constantly feeling that it is being ebbed out into the vast…? Painting, for me, is a way of developing one’s own iconography, a personal metaphorical shield.

That is why I paint.